Small business owners and self-employed people are always looking for ways to maximize their tax savings. The key to legally cutting your business taxes to the bone is knowing the best ways to deduct business operating expenses to produce the very lowest taxable income. That’s the focus of this article. We’ll complete the picture with the rules for writing off assets purchased for your business.

Table of Contents

First, how is your business income taxed?

The U.S. government taxes a business’s profits— so the more you end up with after deducting your expenses, the more taxes. And, ours is a progressive tax, meaning the more you make, the higher percentage of income tax you pay.

So, the American entrepreneur has a strong incentive to keep taxable profits as low as possible, while at the same time taking home as much money as possible.

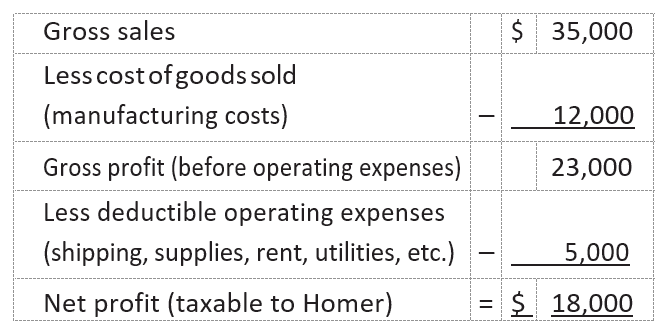

Let’s start with a simple illustration of how net taxable profits are determined in any kind of business operation.

EXAMPLE: Homer quits his job at a nuclear power plant and goes into business for himself making and selling an automated dog walker that he invented. Incredibly, Homer makes money, and at the end of the year determines his taxable profits as follows:

How much Homer will owe in federal (and maybe state) income and self-employment (Social Security and Medicare) taxes on the $18,000 net profit depends on his family’s total income, personal deductions and exemptions.

What Must I Include In My Business’ Income?

Sales only? Bartered goods? Foreign income? Gifts? Ill-gotten gains? Fringe benefits? Inheritances?

Now let’s see what expenses you can deduct from your business income to get your net profit number as low as possible. Keep in mind that all of these deductions are “double tax savers.” They reduce both your income tax and your Social Security and Medicare contributions.

Cash Expenses Are Deductible, But …

Cash expenses may be hard to prove to an auditor without some evidence. The IRS understands that even in a credit card world, cash is still around.

Small things like tips to service folks, cabbies, waitresses, parking lots, postage, subways, and so on are okay. The IRS will be skeptical, however, if you say you bought a Hummer for cash. Expect an annoying “where’d you get the money” question.

You can jot down out-of-pocket cash items at the bottom of your day-timer, and transfer them to Quicken once a month. If you claim over several hundred dollars, make sure you have an explanation of where the cash came from—the petty cash drawer, ATM, or cash sales at your business.

What Is a Deductible Business Expense?

Congress knows you have to spend money to make money. So, the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) says that just about any expenditure that is made to produce business income is deductible. Then, the tax code lays down about a million rules telling exactly how and when you can and can’t deduct things. Luckily, relatively few restrictions apply to the average small time operator.

The Rule for an Expense to Be Deductible

To qualify as a deductible business expense, the expense must be:

• Ordinary and necessary for the business

• Not extravagant, and

• Primarily for the business (not personal).

In other words, money you spend in a reasonable way, with an expectation of bringing in business revenue, is a deductible expense.

Ordinary and Necessary

Okay, so what’s an ordinary and necessary expense for a business? The tax code doesn’t define it. This means we have to look at court decisions and IRS pronouncements for guidance. One judge said necessary means “appropriate and helpful.” Another judge held that ordinary means “normal, common, and accepted under the circumstances by the business community.”

When you consider whether an expense is ordinary and necessary, start with a commonsense approach. Most enterprises need a fixed location, for instance, and paying rent or having a home office is appropriate, normal, and common, and is thus considered both ordinary and necessary.

Sometimes the answer is not as clear. For instance, let’s say Fifi, a real estate agent, takes prospective clients to Chez Chez for $100 lunches and drinks to discuss properties for sale. For her business, this is an appropriate, helpful, and accepted business practice (and justified by the five-figure real estate commissions the lunch could generate). But, if Joe the plumber cleans out someone’s kitchen drain for $75 and then takes his customer out to a $100 lunch, it hardly looks ordinary and necessary. You get the picture.

Some folks try to push the envelope, and the IRS has pushed back. Here’s a tax court case that makes the point.

EXAMPLE: Mr. Henry, an accountant, deducted expenses for maintaining his yacht. The IRS audited him and disallowed these costs. Henry contended that since his boat flew a pennant with the number “1040” on it, it brought him professional recognition and new clients. The court held that a yacht wasn’t a normal expense for an accountant, and so it was neither ordinary nor necessary. In short, the yacht was a (nondeductible) personal expense.

Tip: Does Your Deduction Pass The Laugh Test?

Experienced tax pros can size up a client’s potential tax deduction by asking themselves, “Can the expense be listed without provoking a snicker?” By this standard, you could say in the example above that the judge laughed Mr. Henry out of court.

Not Extravagant

Although there’s no “too big” limitation on business expenses in the tax law, IRS auditors sometimes find deductions out of proportion to the nature of the business. The tax code (IRC § 162) frowns on “lavish and extravagant” expenses, but doesn’t define these terms.

Again, it’s more of a commonsense thing. For instance, it’s fine for The Gap to lease a jet for travel between manufacturing plants, but not for Sam’s Corner Deli owner in Miami to fly to New York to meet with his pickle supplier.

Personal Expenses

The Numero Uno suspicion of the IRS when auditing small business owners is whether purely personal expenses are disguised as business deductions. Did you use business funds to pay for your son’s Bar Mitzvah and deduct it as an “employee party” or as “advertising”?

Other times, it’s not so easy to distinguish between business and personal. Would you think the costs of driving to your office and home again are personal or business expenses?

Well, commuting costs are spent in pursuit of making money for your business, not for personal pleasure—but the tax code says these costs are not deductible. (For more on commuting expenses, see “Commuting Costs,” below.)

Expenses You Can Never Deduct

Certain things aren’t tax deductible—even if they meet all the criteria—because it would violate public policy to encourage these activities. These items include:

• Government-imposed fines, like a tax penalty for making a late filing, a speeding ticket, or a parking ticket

• Bribes and kickbacks, whether to a local building official or an Arab sheik

• Referral payments to get a client or customer, if illegal under a state or federal law, and

• Political contributions or payments to purely social organizations.

(For details, see IRC § 162.)

In addition, the value of services can’t be deducted. For instance, Dr. Pond performs free eye exams for homeless people every Saturday. Normally, the doctor charges $100 for this service. He can only deduct his out-of-pocket expenses, not his time. This would likely qualify as an advertisement and promotion expense.

CAUTION: Payments to relatives (or to businesses owned by relatives) are suspect. It’s okay to hire your kids or parents to do work for you, but payments to them must be reasonable and they have to do real work. Usually, the IRS finds this out by asking you the question or by noticing that the family names of the payees are the same as yours. Sometimes the issue is raised because the expense seems extraordinarily large to the auditor.

Is It a Current or Future Year Expense?

Tax rules cover not only what deductible business expenses are, but also when you can deduct them. Most money you spend on your business

is deductible right away (on the current year’s tax return), but the tax code says that some costs must be spread into future years. Accountants divide this world of expenses into current and capital expenses. How it works is described below.

Current expenses are the everyday costs of running your business, such as monthly phone, rent, and utilities bills. You deduct your current expenses in full from your business revenues in the year they were paid or incurred. Simple.

Capital expenses are costs that will provide benefits to the business beyond the current year. Typically, assets purchased (like machinery, computers, and furniture) must be deducted over a number of years (capitalized). The rationale is that because these assets are used over several years, their costs are spread out to match the business revenue they help earn. Asset purchases are subject to special tax rules.

Gray areas sometimes occur when an expense is incurred to repair an existing asset—is it a current expense or a capital expenditure?

A repair is a capital cost if it:

- Adds to the asset’s value

- Appreciably lengthens the time the asset can be used, or

- Adapts the asset to a different

EXAMPLE: Gunter owns a die-stamping machine that he uses in his business, MetalWorks. He deducts the machine’s routine maintenance costs as a current expense each year. After 15 years, the die-stamper is falling apart. Gunter decides to rebuild the machine. The $80,000 cost to rebuild must be capitalized—it can’t be deducted in one year. The tax code says that metal-fabricating machinery costs are deductible over five years.